Cancer or Cuts? How Technology in Ghana's Cocoa Sector is Designed to Create the Problem It Seeks to Solve

In this piece, I argued how technology within the cocoa sector in producing countries like Ghana is not merely solving problems but instead introducing new crises that will, in time, require further interventions, each one benefiting external actors while diminishing local control.

Technology is often portrayed as a transformative force in agriculture, promising efficiency, increased productivity, and enhanced livelihoods for farmers. While technology has played a crucial role in solving some of the current world’s challenges, its use should be more focused on solving problems, not creating new ones. In the cocoa sector, mechanisation and digital finance solutions are marketed as pathways to prosperity. If you are to research about ways of solving cocoa farmers’ economic livelihood challenges, “outdated technology” becomes the issue that is posed as the cause. However, underneath these optimistic narrative harbours a hidden structural shift that mirrors the social and economic challenges faced by Western industrial economies. While technology may indeed solve some short-term inefficiencies, it systematically erodes the traditional socio-economic fabric that has sustained cocoa-growing communities for generations.

It is essential to clarify what I mean by technology in this context. Farmers have always innovated and introduced new methods to improve efficiency, whether through refining traditional techniques, developing tools for harvesting, or enhancing storage systems. These organic advancements are not the target of my critique. Rather, I am examining externally imposed mechanisation and digital systems that fundamentally restructure cocoa farming in a way that benefits external players at the cost of farmers’ autonomy and traditional economic structures.

A clear pattern emerges from my assessment. That is Technology is introduced → A new problem arises → That problem itself becomes another money-making industry. This cycle can be observed across multiple aspects of cocoa farming, from labour replacement to financial extraction and the breakdown of traditional family structures.

The shift in power over cocoa pricing also fits within this framework. My fight to ensure that farmers are independent and able to set their own prices (decommodification), just as chocolatiers do with their chocolate, is essential in sustaining the traditional way of maintaining community cohesion and equitable wealth distribution. Otherwise, I am tempted to believe that stripping the farmer of pricing power was by design to make technology appear as the only path to individual wealth, thereby isolating the farmer from the community and making them easier targets for external exploitation.

Cocoa farming has historically been a deeply communal activity, with its economic benefits spread across multiple roles. The plucker, pod carrier, pod breaker, fermenter, bean transporter, the cocoa krakye (purchasing officer) all had distinct tasks that contributed to a shared wealth model. This labour stratification ensured that income was intentionally distributed across the community, preventing economic concentration in one man’s pocket and enabling self-sufficient rural economies where everyone eats (not a few in gold plated silverware)

Mechanisation disrupts this equilibrium by replacing human labour with machines. While proponents argue that this leads to efficiency, it instead consolidates wealth in fewer hands, mirroring Western industrialisation, where technological advancement resulted in mass unemployment and widened wealth gaps. Technology through mechanisation as a solution to cocoa farmers and farming community endemic poverty challenges is by design to argue that the farmer should care about their individual self (not even their children) to reduce their expenses by pushing away community beneficiaries. This way, they can see themselves as having increased income, hence poverty alleviation. The elimination of these roles does not translate into new opportunities; rather, it extracts income that previously remained within the community and redirects it to machinery manufacturers, foreign investors, government revenue through taxes, and increased knowledge advancement through research and development, leading to the development of the mechanisation in the foreign country that exports it to cocoa-producing countries.

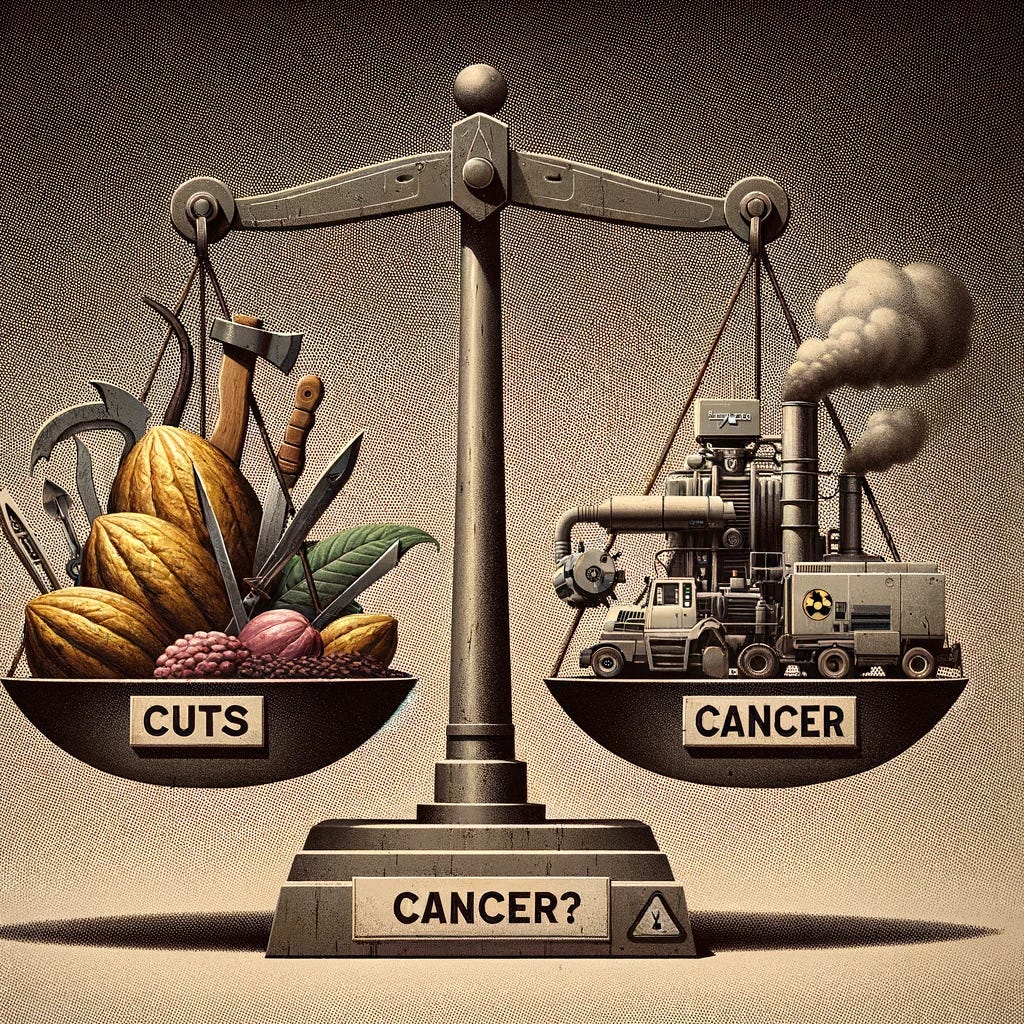

Beyond economic shifts, mechanisation brings a lifestyle change. Traditional farming naturally incorporated physical exertion, providing built-in health benefits. In contrast, Western societies, after replacing manual labour with automation, had to introduce fitness industries as a response to rising obesity and metabolic diseases. The global fitness market, valued at over $96 billion, is a by-product of sedentary lifestyles created by industrial automation. The poor become unhealthy and can’t even afford the gym as a solution. As Ghana moves towards mechanised cocoa farming, a similar pattern is emerging. Farmers who once engaged in active labour will now be pushed toward a more sedentary existence, increasing the likelihood of health issues (cancer, diabetes, hypertension, etc) that previously did not exist in rural Ghana. In a few decades, I may see an emerging market for fitness programs and lifestyle interventions in farming communities as a solution to a problem created by mechanisation itself. I have asked myself several times why the gym is not seen as an abusive place (because people are screaming and paying money to inflict pain on themselves hahaha)

As mechanisation alters farming practices, it also transforms dietary habits. Traditional farming communities have long relied on fresh, whole foods that complemented their physically demanding lifestyles. However, as the structure of work changes and mechanisation reduces labour intensity, processed and fast foods are increasingly marketed as a “cheaper” and more “convenient” option, especially for the one that mechanisation has rendered poor. Let me not even start with the high rise of autoimmune diseases happening in the cities where being more Western means more civilisation. In a country where being westernised has been revered such that the youth in the village aspires to it, you can only feel my concern.

Western societies followed this same trajectory. As industrialisation restructured work patterns and limited the time available for meal preparation, the fast-food industry emerged, not as a luxury but as a necessity. The rich still had maids who could prepare healthy food for them at home. This shift resulted in rising rates of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease. The House of Commons Library in the UK estimates that around 1 in every 4 adults and around 1 in every 5 children aged 10 to 11 are living with obesity These health crises then create massive profit opportunities for pharmaceutical companies, fitness industries, and healthcare providers. The narrative often presented is that fast food has “created jobs” in these industries, yet this overlooks the fact that these jobs only exist because of a crisis that was engineered in the first place.

Ghana is beginning to follow this trajectory. As mechanisation and economic constraints push more farmers toward urbanised, fast-paced lifestyles, dietary habits are shifting toward processed foods. The very people impacted by this dietary transition, the poor and vulnerable, become the primary consumers of cheap, unhealthy food, much like how Western industrial workers became the primary market for fast food. This pattern does not just create a health crisis; it opens the door for what I call bad faith benevolence, where the same corporations and interest groups that contributed to the problem come forward with solutions, profiting twice from the crisis they helped create. Just as fast food companies fund obesity awareness campaigns and pharmaceutical companies market diabetes treatments, I foresee a future where multinational health corporations step in to “help” with the health crises emerging in Ghana, soon in the villages, all while ensuring their financial stake in the system remains unchallenged.

The economic restructuring caused by mechanisation is not just limited to diet and employment, it extends deeply into financial extraction. Mobile money services, marketed as a solution to financial inclusion, have become another avenue of wealth extraction from cocoa farmers. The narrative is that mobile money protects farmers from cash theft, but in practice, it serves as another mechanism of financial control by telecom companies. Mind you, just at the end of the 1st quarter of 2024, MTN recorded a

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cocoa Diaries Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.