Why Are We Ignoring the Unpaid Support Systems That Keep Cocoa Farmers Alive?

In Ghana, cocoa farming has long been praised for its contributions to the economy and for providing opportunities for rural families. The narrative that cocoa has lifted countless families out of poverty, enabling children to attend school and learn English, is one that is often repeated, both within Ghana and abroad. At first glance, it appears as though cocoa income is the bedrock upon which these opportunities are built. Yet, as I reflected during a conversation with friends recently, this narrative is far too simplistic and largely ignores the complex social and communal systems that are crucial to the survival of cocoa farmers.

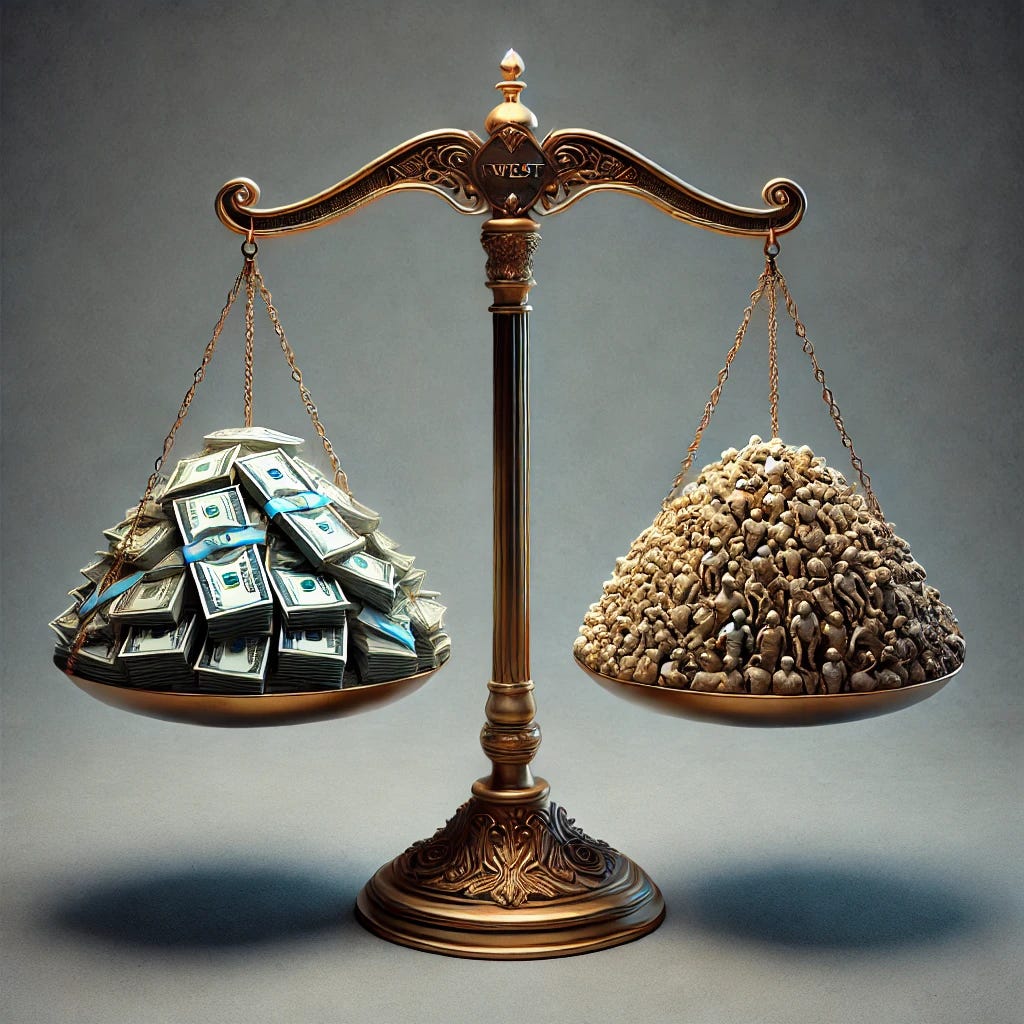

The truth is that the smallholder cocoa farmer in Ghana is caught in a deeply exploitative system, one that overlooks the unpaid social structures and instead focuses solely on the financial benefits of cocoa. These farmers are surviving, not because of cocoa alone, but because of a deeply rooted support system that allows them to meet their basic needs without spending the limited income they receive from selling cocoa beans. By ignoring this reality, we perpetuate the illusion that cocoa income is sufficient, while in fact, these farmers are kept at a subsistence level, shouldering the burden of global cocoa demands with little to show for it.

Social Support Systems

One key issue is the undervaluation of the informal social support systems that are vital to the lives of cocoa farmers. In rural Ghana, farmers do not rely solely on cocoa income to survive. They grow cassava, plantain, garden eggs, yams, and other crops that feed their families. They rely on communal childcare and shared labour arrangements. In other words, their livelihood is not sustained purely by the money earned from cocoa but by a complex network of unpaid systems that allow them to meet their everyday needs without having to pay for services that would be monetised in urban or Western settings.

Let us put this into perspective. In cities or in more developed countries, everything costs money. Food must be bought from the grocery store, childcare services are paid for by the hour, and even the time it takes to travel to work is monetised. Now imagine asking someone in Europe or the United States to plant their own food and care for their children through communal networks, all while being paid a fraction of the wage they currently earn. The outcry would be immediate, and yet, this is precisely what Ghanaian cocoa farmers are doing. They are expected to be grateful for the little they earn from cocoa, while the invaluable, unpaid contributions of their social networks are ignored.

This dismissal of the value of these systems creates a distorted picture of the farmer’s reality. It allows corporations, governments, and even some advocates of cocoa farming to claim that cocoa provides immense benefits to farmers, when in practice, it is their social structures and subsistence farming that are keeping them afloat. This should force us to question: why is the value of unpaid social contributions set at zero when they are fundamental to the survival of these farmers? Why is the ability to send a child to school or afford basic healthcare attributed entirely to cocoa income, while the unpaid work that makes this possible goes unnoticed?

Low Wages for Farmers, Higher Wages for Western Workers

Beyond the undervaluation of unpaid social contributions, there is the issue of the global cocoa market itself, which is structured in a way that keeps farmers underpaid to benefit wealthier economies. One glaring example of this imbalance is the wage gap between a Ghanaian cocoa farmer and a factory worker in a chocolate-producing country like Switzerland. Why should a cocoa farmer, who is doing the physically demanding, labour-intensive work of growing and harvesting the cocoa beans, earn a fraction of what a chocolate factory worker makes in a country like Switzerland, where living costs are higher?

The argument often presented is that the cost of living in Ghana is lower, so farmers do not need to earn as much. But this argument falls flat when we consider the amount of unpaid labour that goes into keeping those farmers afloat. A farmer in Ghana may not be paying for childcare or food in the same way a worker in Switzerland might, but that does not mean those services are without value. So why should one be allowed to capture more value to cater for their cost of living but the other should still leverage barter trade of support systems in their country to deal with their problems too. The Ghanaian farmer is being paid less precisely because they are subsidising their own survival through unpaid labour and communal support systems. The international market benefits from this arrangement because it keeps costs low in cocoa-producing countries, allowing for higher wages in chocolate-producing countries.

Imagine if we flipped the script. If factory workers in Switzerland were paid the same wage as cocoa farmers in Ghana, the disparity in living conditions would become glaringly obvious, innit. Those workers would quickly push back against such a low wage, recognising that it would not allow them to meet their basic needs. Yet, this is exactly the situation that cocoa farmers in Ghana are living with, subsidising the higher wages of others by shouldering the burden of their own unpaid work and under compensation.

Hidden Value of Communal Support

Another point that is often missed in discussions about cocoa farming is the value of communal support systems. In rural Ghana, families often share the burden of childcare, allowing farmers to work in the fields without worrying about paying for professional childcare services. This communal system is an enormous financial relief for families, yet it is never factored into the discussion of cocoa incomes.

Now consider how this plays out in an urban or Western context. Childcare is one of the largest expenses for working families in many parts of the world, costing thousands of pounds or dollars per year. This cost is factored into wages, ensuring that workers are compensated enough to cover the expense. In Ghana, however, the communal support system means that farmers are not paid more simply because they do not have to pay for childcare. Yet, this does not mean that the value of that childcare is zero. It simply means that the financial burden has been transferred away from the formal market and into the unpaid labour of the community.

Similarly, the food that farmers grow for their families like cassava, plantain, garden eggs, pepper, maize, etc plays an essential role in sustaining them. They do not have to buy these staples from the market, which means they can use the limited income from cocoa to cover other expenses. But again, just because this food is not bought does not mean it lacks value. The ability to grow food for oneself is an economic advantage, and it is precisely this advantage that allows cocoa farmers to survive on such low incomes. In a Western context, food is bought and paid for, and salaries are adjusted to cover these costs. So why is it acceptable to ignore the economic value of food grown by farmers themselves in Ghana?

Who Really Benefits?

At the heart of all these issues is the question: who is truly benefiting from the current cocoa system? It certainly is not the farmer. The multinational corporations that dominate the cocoa trade benefit from keeping prices low and wages in Ghana suppressed. The chocolate industry, worth billions, relies on cheap cocoa from countries like Ghana to keep its profit margins high. And while cocoa farmers continue to live on subsistence incomes, the industry celebrates its "sustainability initiatives" and "fair trade" practices, which in reality do little to change the structural inequalities in the system.

In the end, it is the unpaid social systems in Ghana that allow cocoa farmers to continue working at such low wages. By growing their own food, sharing childcare responsibilities, and relying on community networks, farmers are able to survive despite being underpaid. But these social structures are not infinite, and their continued existence cannot justify keeping cocoa prices artificially low. If the global cocoa industry truly wants to support farmers, it must begin by recognising and valuing the contributions of these unpaid systems. Only then can we begin to address the deeply embedded inequalities that keep cocoa farmers in poverty.

So the current narrative around cocoa farming in Ghana is incomplete. By focusing solely on the financial returns of cocoa income, we ignore the critical role that unpaid social support systems play in the survival of cocoa farmers. These systems whether it is the food farmers grow for themselves or the communal childcare they rely on are essential to their livelihood, yet they are valued at zero in global discussions. Meanwhile, farmers are paid less to subsidise the higher wages of workers in wealthier countries, and the corporations that dominate the cocoa trade continue to profit from this inequality.

There needs to be a fundamental shift in how we think about cocoa farming. We must recognise the invisible contributions that make it possible for farmers to survive on such low incomes, and we must challenge the structures that perpetuate this exploitation. Only by addressing these deeper issues can we create a cocoa industry that is truly just and sustainable for all.