The Cocoa Inequality Trap: By Design, Not by Accident

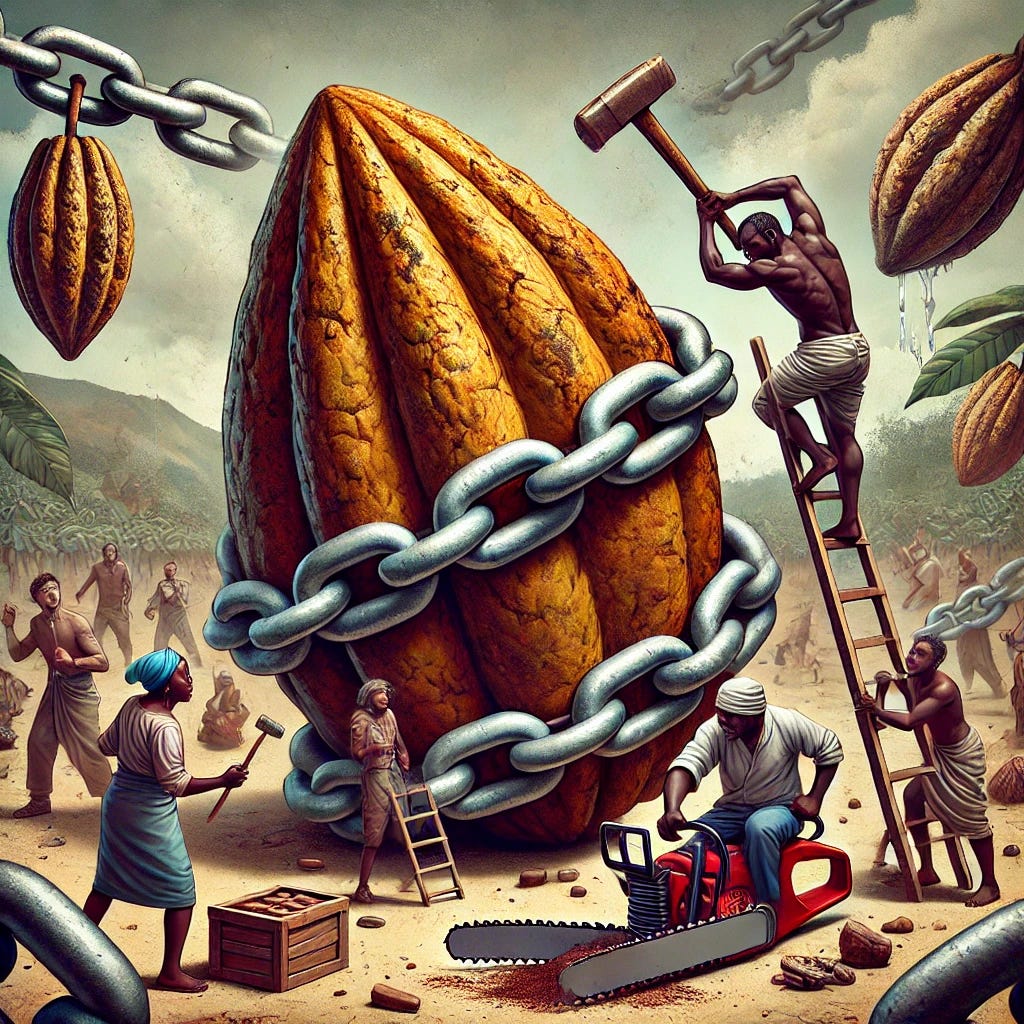

It can be argued by many that the ongoing inequality in the cocoa sector, where farmers remain trapped in poverty despite the billions generated by the industry, is merely an unfortunate consequence of market forces, inefficiencies, and unpredictable price fluctuations. But what if this inequality is not an accident? What if, instead of being an unintended crisis, it is actually the product of a carefully designed system that ensures cocoa-producing countries and their farmers remain at the bottom of the value chain?

When discussing the plight of cocoa farmers in Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and other producing nations, many tend to attribute the situation to external economic shocks, lack of infrastructure, or even poor financial literacy among farmers. However, a deeper look into the history and structure of the global cocoa trade reveals something far more unsettling: this inequality is systemic, built over decades through policies, pricing models, and corporate structures that concentrate value in the hands of a few.

Others may also argued by many that cocoa-producing countries cannot simply process and market their own cocoa at scale, hence their continued reliance on exporting raw beans. But this reasoning ignores the intentional obstacles placed in their way. Below are a few arguments that hopefully I can use to convince you that we are not in a broken system, rather we are in a perfectly design system aimed at generating the outcomes we are experiencing. Let me explain.

The Price Control Mechanism That Never Favors Farmers

Farmers have no control over the price at which they sell their cocoa. Unlike chocolatiers who set prices for their finished products, farmers rely on global commodity markets, where cocoa prices are determined by speculative trading rather than production costs or farmer well-being. This means that, even when cocoa prices rise, the increase is often absorbed by multinational corporations and middlemen, while farmers see little to no benefit.

It can be argued that markets fluctuate “naturally” (which we know is not true), and price volatility is part of the business (when it’s a convenient argument for us to make), but who truly benefits when prices drop as a result of increased production when chocolatiers invest in initiatives to cause increased production in producing countries? Multinational corporations, hedge funds, and major processors hedge their risks through diversified investments and contracts that shield them from market shocks. Farmers, on the other hand, bear the full brunt of price crashes with no safety nets.

The Reluctance to Support Local Cocoa Processing

One would assume that increasing processing capacity in cocoa-producing countries would be encouraged as a means of breaking free from dependence on raw bean exports. But if this is such an obvious solution, why hasn’t it happened on a large scale? The reality is that trade policies and corporate structures actively discourage local value addition. Yes, cocoa processing in Ghana and Ivory Coast is on the rise by multinationals. It's amazing, right? we fought great, right/ Well, let me break it to you: the increased processing capacity was due to farmers as citizens being made to finance these corporations through the Ghana Freezones incentives. The farmer pays the taxes, and the chocolate is not made to pay. The farmer builds the road to make their country attractive for value-addition. Oh, I forgot to add that we provided a 20% reduction on light crop beans as well in Ghana as an additional means to attract value addition locally. And Oh I forgot to add that the cocoa beans and the processed cocoa products magically got their import tariffs to Western countries almost removed but chocolate importation from Ghana has its tax as fixed as the system.

Western economies impose high tariffs on processed cocoa products from producing countries while allowing raw beans to enter duty-free. This disincentivises local chocolate production, keeping Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire as raw material suppliers rather than global players in the finished product market.

It can be argued that producing countries have the option to invest in their own chocolate industries, but without access to high-value markets and with tariffs eating into potential profits, such ventures struggle to scale. Meanwhile, multinational corporations benefit from cheap cocoa that they can process in their own factories for significantly higher margins.

3. Certification Programs That Do Not Serve Farmers

Another layer of the inequality trap is the certification schemes that claim to promote sustainability and fair pay. Consumers in Western countries often pay premiums for certified chocolate, believing they are contributing to a fairer industry. However, the reality is that the majority of these premiums never reach the farmers themselves.

It can be argued that certification schemes create a more ethical supply chain, but if this were true, why do so many farmers remain in poverty? Many of these programs function as branding tools for multinational corporations rather than mechanisms for real financial improvement. The added costs and bureaucratic requirements often burden farmers more than they benefit them.

How Farmers and Producing Countries Can Reclaim Their Power

The good news is that this system, while deeply entrenched, is not unchangeable. Cocoa-producing countries and farmers are not powerless, and with the right strategies, they can begin to dismantle the structures that have kept them economically suppressed. But what can they do

1. Strengthening Regional Collaboration for Price Control

One of the most effective ways to push back against the pricing model is through regional alliances. Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, which together account for over 60% of global cocoa production, have already begun working together to demand better prices (LID). Expanding this collaboration to include other producers can create a stronger bargaining position against multinational buyers.

It can be argued that countries have tried to unify before without success, but unlike in past attempts, current moves are being supported by growing consumer awareness of exploitation in the chocolate industry. If producing countries can leverage this awareness, they may be able to enforce a system where cocoa prices reflect the actual cost of sustainable production. Of course anytime, centralisation happens, corruption becomes much bigger so let’s say this is not that potent.

Investing in Local Processing and Global Branding

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cocoa Diaries Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.