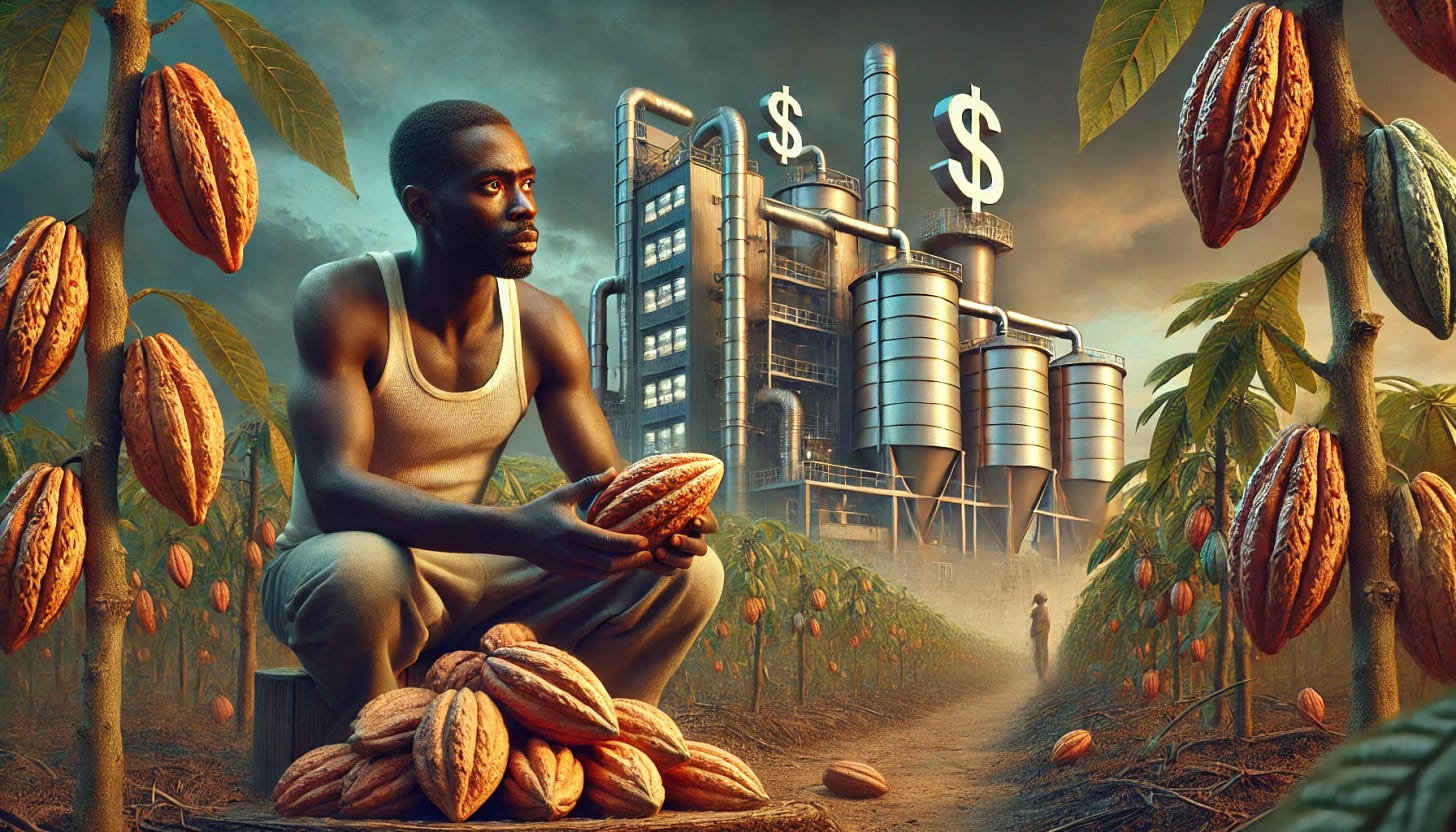

Tax Breaks for Some, Burdens for Others: The Dual Reality of Ghana’s Free Zones Policy within the Cocoa-Chocolate Value Chain

Let’s revisit Ghana Freezones as a Policy that had intentions whose unintended consequences overshadowed it in the Ghanaian cocoa-chocolate value chain.

The introduction of Ghana’s Free Zones policy in the mid-1990s was a strategic attempt to accelerate export-driven industrialisation, attract foreign direct investment (FDI), and enhance value addition in key export sectors, including cocoa. Designed with generous incentives such as tax holidays, duty exemptions, and unrestricted capital repatriation, the policy aimed to position Ghana as a competitive global processing hub. From a political perspective, however, the outcomes of this policy have been shaped by the interests, power asymmetries, and interactions among key actors, that is the state, multinational corporations (MNCs), local cocoa farmers, and indigenous processors. This article will explore how these interests aligned or conflicted, resulting in both intended and unintended consequences with significant implications for Ghana’s cocoa sector which leaves the farmer to shoulder all the negatives of it.

Ghana’s cocoa sector has long been central to its economy, contributing approximately 25% of foreign exchange earnings, with over 800,000 smallholder farmers as the backbone. Recognising this strategic importance, policymakers viewed the Free Zones policy as a mechanism to increase domestic processing capacity and enhance export revenues through value-added cocoa products. However, from a political perspective, the state’s interest in maintaining fiscal stability and securing external advantages from multinational companies often conflicted with the welfare of local actors, particularly smallholder farmers and Indigenous processors.

Multinational corporations such as Barry Callebaut, Cargill, and Olam leveraged the Free Zones policy to establish cocoa processing plants in Ghana. These corporations were attracted by the proximity to raw materials, reducing logistical costs and ensuring a reliable supply chain. However, the operations of these firms reveal a crucial flaw in the policy: while cocoa processing physically occurs in Ghana, the financial benefits largely accrue outside the country. These MNCs operate as subsidiaries of global conglomerates, with sales, marketing, and financial transactions managed by headquarters abroad. Consequently, although production figures are recorded locally, foreign exchange earnings remain offshore, undermining one of the policy’s primary objectives, i.e. to increase our foreign exchange. I inquired officially from the Ghana Free Zones Board to confirm how they assess our reception of the foreign exchange from these firms in Ghana. They confirmed that foreign exchange earnings are measured based on production value rather than actual cash inflows into local banks, further complicating efforts to track economic benefits.

A critical aspect of this article is understanding how power relations influence the distribution of benefits within the value chain. In this case, the Free Zones policy has disproportionately favoured Multinational Corporations, who wield significant bargaining power due to their control over global cocoa markets. These corporations extract undue benefits by capitalising on tax incentives and low production costs (due to low labour, proximity to supply, reduced shipping costs due to low volume and high value expect, etc) without contributing commensurately to the local economy. For example, despite benefiting from subsidised utilities and infrastructure, most MNCs retain profits abroad (because the policy allows them the opportunity to do so) hence limiting Ghana’s foreign exchange gains and the circulation of such turnovers in the country to to boost the economy.

Employment creation, a key policy justification, has also been underwhelming. While initial projections anticipated significant job growth, many processing plants are highly automated (Known of cocoa processing factories), requiring minimal human labour. Without stringent labour regulations mandating local employment quotas in both senior and middle-level management, firms will rightfully prioritise capital-intensive operations to maximise profits. This approach aligns with the broader profit-driven motives of MNCs but contradicts Ghana’s development goals of employment generation and poverty reduction through the freezone policy. Moreover, Ghana’s ambition to become a digital hub in Africa creates policy tension: enforcing labour-intensive practices may conflict with technological advancement agendas, leaving policymakers in a bind.

The infrastructure required to support Free Zones companies such as roads, electricity, water, and port facilities is largely financed by Ghanaian taxpayers, including cocoa farmers. This creates a financing paradox: local stakeholders, particularly smallholder farmers, indirectly subsidise foreign investors through taxes yet derive limited direct benefits. The state’s prioritisation of infrastructure development for Free Zones companies has often come at the expense of rural communities, where inadequate infrastructure continues to hinder productivity.

More

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cocoa Diaries Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.