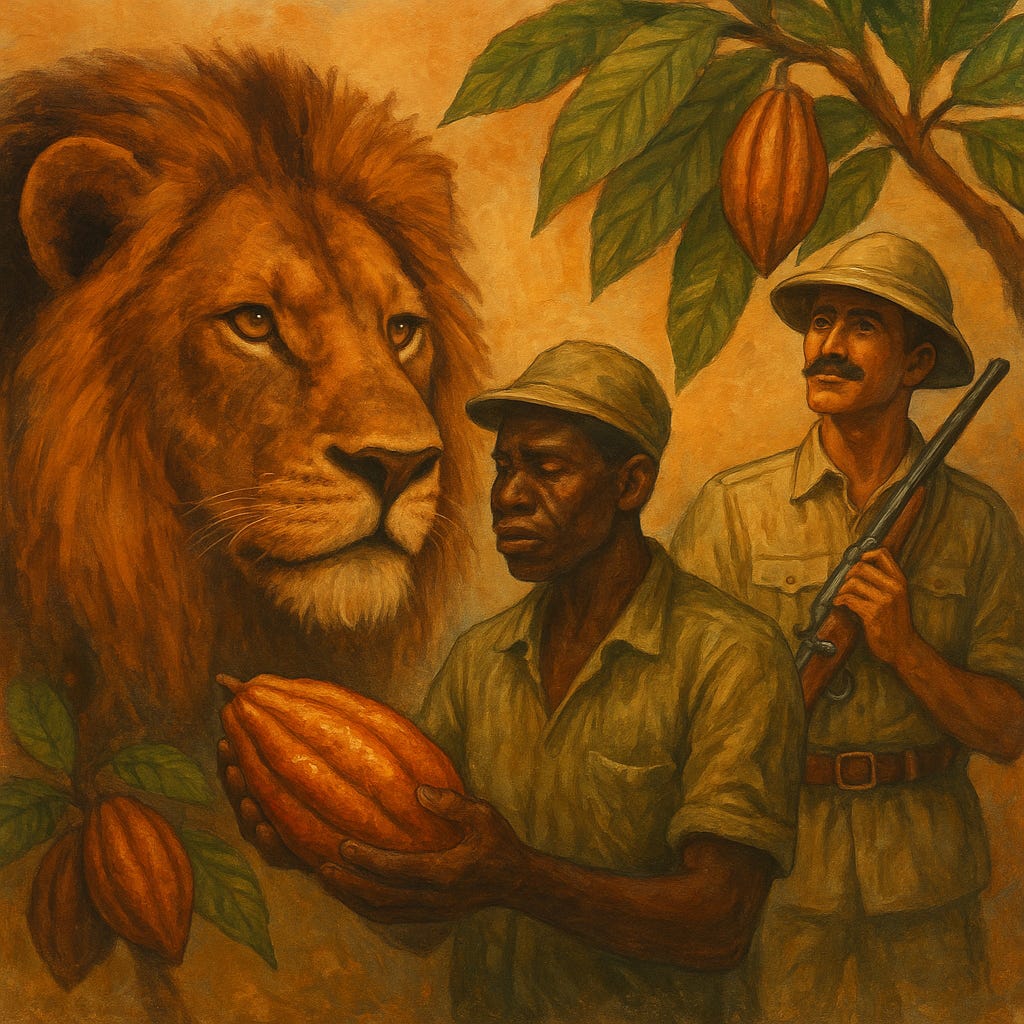

Part 4: Until the Lion Tells His Story (The Cocoa Farmer)

…….. Global Parallels and the Way Forward

“Until the lion tells his story, the hunter will always be the hero”

Throughout this series, I have shared the story of Ghana’s cocoa farmers – my father’s story – of working hard yet remaining poor, of being marginalised by structures that should protect us, and of contributing so much value yet receiving so little. Now I want to connect our struggle to the wider world. The inequities in the cocoa sector are not unique; they echo in the experiences of gig workers, small farmers, and labourers across the globe. By drawing these parallels, I hope to show that what we are fighting for is universal: fairness, dignity, and a voice in our own destiny. And I will not shy away from calling out the hypocrisy of those who speak of equity, diversity and inclusion in boardrooms while turning a blind eye to exploitation on the farm.

Consider the Uber drivers in London I mentioned earlier. For years, the tech company insisted these drivers were independent contractors – effectively denying them benefits like holiday pay or a guaranteed minimum wage. It took a Supreme Court ruling in 2021 to set things straight: the court unanimously held that Uber drivers are workers, entitled to basic rights. The judges saw how tightly Uber controlled the drivers’ work (setting fares, managing assignments) and declared that attempts to “sidestep basic employment protections” were void. One union leader’s words resonated with me: “Uber drivers are cruelly sold a false dream of endless flexibility and entrepreneurial freedom.” Doesn’t that sound familiar? Our cocoa farmers, too, have been sold the false dream that they are independent entrepreneurs in full control, when in fact they bear all the responsibility with few of the rewards. The lesson from London is that legal recognition and collective action can force a rethinking of such injustices. Ghana’s cocoa farmers may not take COCOBOD to court in the same way, but the principle stands: those who work should not be denied basic rights and a fair share of value under the guise of “independence.”

Next, look at small farmers in India. In 2019, the Indian government launched the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Maandhan Yojana – a pension scheme for small farmers. On paper, it sounded generous: contribute a tiny amount (around Rs 100 monthly, about £1) and get a pension of Rs 3,000 per month (about £30) after age 60. But it was voluntary and required farmers to sign up and contribute regularly. The target was 50 million farmers; by early 2025, only 1.9 million had enrolled – a mere 4% of the goal. Why the abysmal uptake? Because many Indian farmers simply couldn’t afford to put money aside, or didn’t trust that the promise would materialise decades later. Over 50% of Indian farming households are in debt, with average debts of Rs 74,000. Asking such farmers to save for a pension is, as one analyst noted, “unrealistic”. A farmers’ rights activist in India went further, calling contributory pension schemes for the poor “impractical” and arguing that “pensions are a human right and should be universal”, indiaspend.com. This echoes strongly for me. Ghana’s cocoa farmer pension, as we discussed, takes money from already poor farmers – effectively a self-funded scheme for those least able to fund it. Perhaps we should heed that Indian activist’s call: true social security for farmers might need to be non-contributory (or at least heavily state-subsidised), acknowledging that forcing contributions in the face of poverty doesn’t work. India’s experience shows that without robust support, farmers won’t or can’t buy into such schemes.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cocoa Diaries Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.